Letters to the Mayor of Seoul/Pyongyang: Seoul Biennale 2017

Letters to the Mayor of Seoul/Pyongyang: Seoul Biennale 2017

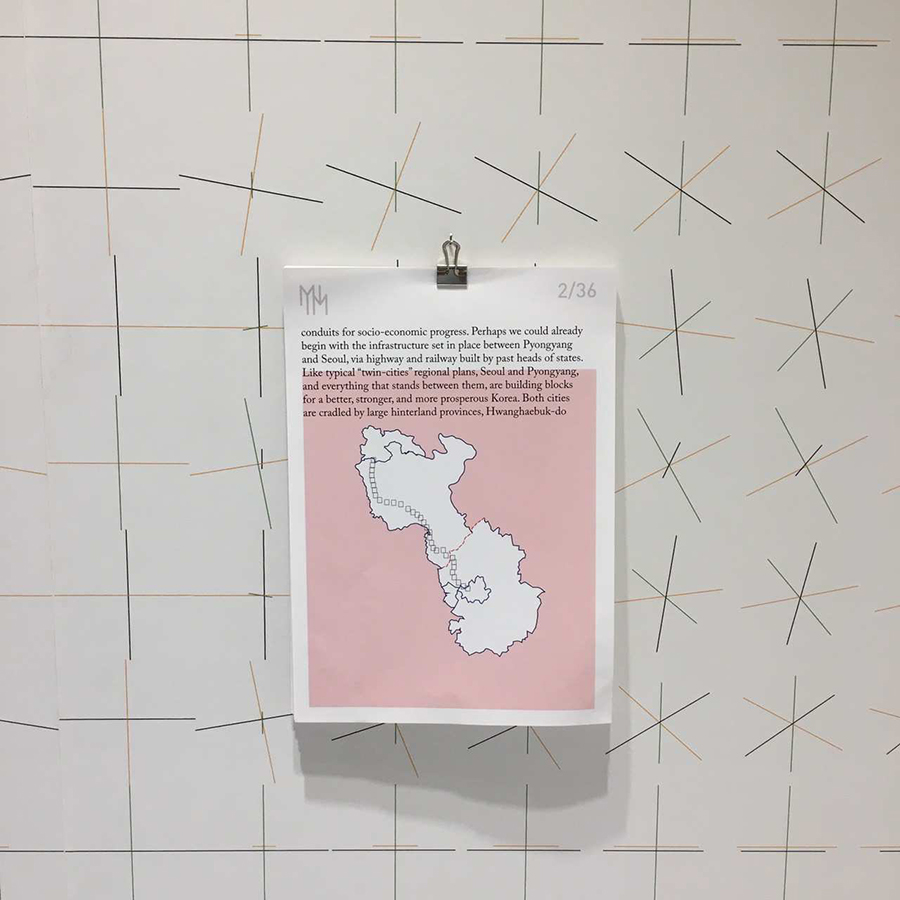

Note: Letters were exhibited as part of the Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism 2017, included in the Cities Exhibition. To the Mayor of Pyongyang Dear Mayor, the Korean Peninsula. It is at the heart of East Asia, and its stability is crucial to the well-being of the continent. As far as the last few generations can recall, the same old politics have done little to improve the impasse between the two sides. What do you think is going to happen if we continue with the same, tired old maneuvers? We believe the answer lies in a critical study of the Korean landforms, and their potential as platforms and conduits for socio-economic progress. Perhaps we could already begin with the infrastructure set in place between Pyongyang and Seoul, via highway and railway built by past heads of states. Like typical “twin-cities” regional plans, Seoul and Pyongyang, and everything that stands between them, are building blocks for a better, stronger, and more prosperous Korea. Both cities are cradled by large hinterland provinces, Hwanghaebuk-do and Gyeonggi-do, which are rich in resources and a balanced expanse of fertile land and mountains. At the northern terminus, Pyongyang’s immediate access to waterways along Taedong River and ultimately Nampo Seaport at the Korean Bay is rivalled only by the rudimentary but well-conceived land transport networks that connect the capital to primary and secondary industries in the provinces. The surrounding suburban counties like Kangnam provide access to farming and light industries due to the flat and vast Pyongyang Plains. Others like Chunghwa County further along this corridor to Seoul provide immediate relief to future conurbation pressures in Pyongyang. The small county towns will eventually be new-town growth centers and facilitate accommodation and business travel between Seoul and Pyongyang. The border with North Hwanghae Province is characterized by mountainous terrains and truncated valleys. Not only are these conditions optimized for a more nuanced agricultural composition and land-use, it also creates a dramatic backdrop for the propitious cooperation between Seoul and Pyongyang. This important region is also one of the many cultural glues of the Korean people, home to many historical relics and dynasty-era cities like Hwangju. Even the nearby Hwangju Airbase could eventually be decommissioned and converted into an educational platform for future generations. Its strategic location could also be converted to civilian use by providing access beyond these mountainous zones. Such infrastructural centers are crucial as hub-and-spoke developmental models, not just for economic growth but other related enterprises like reforestation programs to replenish the extreme denudation of forests for firewood especially during the harsh winters after the war. The provincial capital of Sariwon at midpoint stands to gain the most from a coordinated Seoul-Pyongyang economy, as its existing framework will administer the flow of goods and services and all supporting industries in the development corridor. Because of the natural valleys around this city, atmospheric pressures create topographic uplifts and wind funnels from areas of high pressure to low. While the winters bring frigid, unforgiving winds from Siberia, the predictable and sustained gusts are perfect conditions for wind energy farms, possibly enough to power the entire region if not the northern half of Korea. If the stability and security of Korea is enabled and ensured, cheap energy and flat lands can be harnessed as real estate for the newest building typology of the 21st century: data centers. Giant arrays of computer servers have a curious effect of upending the chicken and egg game of investment attraction versus good governance. With data centers, everybody wins (be careful with the environment!) and society can take another tiny step forward. Indeed all of this is for naught if we do not take steps to reverse the decades of inaction in managing the environment. Green zones must be legally demarcated and budgets earmarked for their care and expansion. Realistically, however, all environmental approaches must be done under the rubric of nuclear management, as illustrated by the much-discussed Pyongsan facility for the mining and refinement of uranium, and its corresponding tailings pond i.e. mining dump. The combined effects of this activity is utter devastation of the area, and if left unchecked, will compromise, or even derail any efforts for regional cooperation. Such are the high-stake exigencies the people of the peninsular must face, but if the desire for a common good trumps the zero-sum game of politics, then a seemingly endless meandering path becomes a clear and direct route to achieving progress. Yes, easier said than done, hence the saying part requires meticulous short and long term plans, while the doing part requires a series of small, achievable and mutually beneficial projects. For example, valley watersheds and regional rainwater drainage basin systems can be improved at marginal cost to provide not just uninterrupted clean drinking water to the nearby population areas, but also to the nearby Kaesong Industrial Region, the first truly successful cooperation between the North and the South. Additionally this will positively impact the residents who currently rely on the heavily polluted groundwater affected by nuclear and industrial activities. Ultimately, the future of the Korean Peninsula lies in your hands; through smart land use and holistic planning, particularly in a Pyongyang-Seoul regional development corridor. The concerted efforts that focus on the productive capabilities and economic performance here will have a ripple effect throughout the peninsular and eventually East Asia. This smart land use will also trigger more demand for an even more sustainable future, as both sides begin to truly see the benefits of joint cooperation. Asymmetrical development in Korea will benefit no one, and can only lead to a violent downward spiral. It is dismal irony that the most contact the North and South currently have is a heavily militarized De-militarized zone where both sides attempt to outdo each other’s bravado. This is not and must not be the exemplar of Korean rendezvous, and certainly not trivialized into a tourist attraction for any top-dollar-paying excursionist. Hence it is not unreasonable to think that a more admissible form of ingress is the de-pressurization of Seoul/Gyeonggi’s rapid urbanization northwards into areas that could benefit from the positive spillover effects. Meanwhile, existing Metro-Seoul suburb cities like Paju will have the opportunity to focus on internal urban rejuvenation and expand on their global competitive advantages, like its billion dollar book industry. The reality is that these areas around Metropolitan Seoul have one of the highest population densities in the world. 25 million people! That is roughly the size of Korea’s neighbor down the pond, Taiwan. Unlike Taiwan, space in Korea is not a premium – but the strategic use of land is. One might go so far as to say that its future depends on it. Luckily for us we all want the same thing. Not so luckily for us, realpolitik only really works when ideologies are compatible with one another. Perhaps the ends may justify the means, but can we agree on what the ends are? So we wish you all the best, and thank you for your time. Yours sincerely, Min Ter Lim, MIIM Office for Architecture, Taipei

-

Client

Storefront for Art and Architecture, Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism

-

Location:

Seoul, South Korea

-

Year:

2017

Share project